Forensic Anthropology and Research - A chat with Dr. Janna Andronowski

Dr. Janna Andronowski

Forensic anthropologist and faculty member in the Division of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine

Sydney Quinn Chizmeysha (SQC): Can you describe your position/field and what does your general work entail?

Dr. Janna Andronowski (JMA): Yes, absolutely. I describe my job as having three arms – I am a faculty member in the Division of Biomedical Sciences, the Anatomy Lead for Undergraduate Medical Education here at MUN (Phases 1 and 2), and the Forensic Anthropologist for the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Each of these roles are quite different, but I use common aspects of my training in each of them.

In terms of my field, I am a skeletal biologist. This falls under the umbrella of biological anthropology, which is a very broad discipline with many subdisciplines. My training is formally in the biological sciences as well as biological and forensic anthropology. What you will learn about forensic anthropologists is that we all had different trajectories towards how we got to our roles. For example, my undergraduate degrees are in biological sciences and criminology. The advice I was given from my first mentor at Simon Fraser University was that if you want to be a forensic scientist you must become a hard scientist first. Study biology, chemistry, physics, math and then specialize – I thought this was good advice. And so, I did the criminology degree to supplement my interests in the forensic fields. From there, both my master’s and doctorate degrees specialize in biological anthropology. That was my trajectory, but in terms of my day-to-day roles, that depends on the day.

“When you are presented with fragments of bone, it is a puzzle … Bone is a living record that retains details about individuals’ lives, and this posed a unique challenge to me”

SQC: When did you start becoming interested in your fields?

JMA: An interesting fact about me is that I am one of those rare people who is doing what they always wanted to do. I was always interested in the mechanics of how things worked and how complex the body was anatomically. Early in my childhood I dissected teddy bears under a microscope [LOL] … I wanted to know how organisms lived and died. So, I always knew I wanted to be in the biological sciences.

I was initially on the track to become a physician; I was pre-med all the way through my undergraduate career and wrote the MCAT for medical school with the intention of pursuing forensic pathology. But in my last year of my undergraduate, I took a human osteology class and that changed my whole trajectory…

When you are presented with fragments of bone, it is a puzzle. Which bone is it from the 206 bones in the human adult skeleton? What side of the body is it from? What can it teach us about this individual’s life? Bone is a living record that retains details about individuals’ lives, and this posed a unique challenge to me. I realized that changing my trajectory to pursue this field [forensic anthropology] would probably be harder as it is quite – I hate to say that it’s narrow – but it is! There are few job opportunities that solely involve forensic anthropology. A lot of us work at universities or as curators at museums and provide external consultation on the side – which is what I do. At the time, I didn’t have that training so I knew it would add to my educational trajectory... I am glad I did it because here I am!.. But it was a lot of hard work to make that change.

SQC: Yes, a lot of hard work has clearly paid off for you!

SQC: So throughout your training and trajectory, what has been your most influential success factor?

JMA: That is an interesting question because I think there have been so many different variables that can impact one’s success. For me, I have to say it has been the support of my fantastic mentors. The most influential has been Dr. Christian Crowder whom I met at a forensic bone histology course as a biology undergraduate student interested in forensics – specifically, bone histology. I took this course and learned so much from everyone involved… I spent some recreational time with the instructors as well and it was during that time that I met Christian. We talked about potential internship opportunities in New York City where I could get involved in a bone histology related project. From there, honestly, the rest is history. I went to New York City and learned everything I know about bone histology.

I have also been influenced by several very strong, smart, and successful women. Namely, my master’s supervisor Dr. Susan Pfeiffer who is a world recognized bioarchaeologist and skeletal biologist. Dr. Amy Mundorff who is a forensic anthropologist, and was the first one, at the OCME in New York City! She was a first responder for 9/11 and organized and coordinated a large team of forensic anthropologists to respond to that situation, and Dr. Lynne Bell, a specialist in bone microscopic taphonomic processes, and my undergraduate mentor who first introduced me to the field of forensic bone histology. These women went through this particular field in a different time. While it is still challenging for us as women in science, it was much more challenging for them…I feel like aspects from all four of those mentors have shaped my mentoring style.

SQC: That is awesome, thank you for sharing those experiences. As your student, I can definitely say you have been that kind of influential role model for me.

JMA: Well, thank you. Again, we are colleagues. I am regularly in touch with my mentors, even still… You know, [my students] are trainees, you are our colleagues of the future and I see you all as exactly that.

SQC: Thank you for that perspective! I know there are some out there who don’t see it that way so it is very appreciated.

JMA: Definitely… I would say I am a product of my academic upbringing. Once you meet my mentors, it will put me in a context that I think makes a lot of sense. We are very similar in more ways than one.

SQC: What was the biggest challenge you have faced in your career thus far?

JMA: I would say, what is challenging about an academic trajectory in general is that you must be adaptable, flexible, and willing to sort of uproot yourself for the opportunities that come your way. That can be very challenging for people depending on individual circumstances. For example, I have lived in 5 provinces, 3 states in the USA and in the UK for a bit, but I was in a position where I was able to do so... I didn’t have life situations or circumstances that limited my ability to move to new places. I find that to be an issue in academia in general… If you are not willing or able to be flexible, it can be very limiting.

For me as a mentor, it is really important to relay these real aspects of what this job is like: time, commitment, flexibility. You may have to sacrifice other things… I have learned a lot in every place that I have lived, and I don’t regret it. It has been the right choice for me, but it might not be for [everyone].

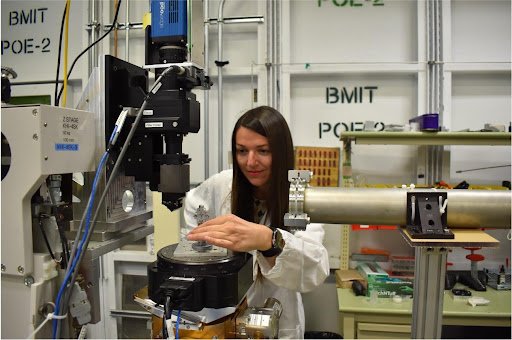

SQC: What part of your work do you enjoy the most?

JMA: For me, it is the hands-on applications in all three of my [fields]…I am not happier than when I am in the lab, working with bones, and trying to solve whatever mystery that I am presented with, or, working to come up with a new protocol for sectioning, studying, or imaging bones. That work still gets me so excited, and when I am in the lab, it reminds me of why I am a scientist. That is why I find when I get bogged down in administrivia I will go to the lab to see what you all are doing, I will poke around and look at the new specimens in my collection. It just brings me back to where it all started for me because, as a trainee, you spend most of your time in the lab. It’s the same thing with teaching anatomy, for example! I love teaching in the lab! It brings me back to that happy place.

Interestingly, I also love writing grants, which is a learned skill. I know a lot of people don’t love [grant writing]… I love writing and reading because there is always new work out there. I have this ‘ideas journal,’ and I write down any and all research ideas that come to me. And, you know, half the time I just do a quick literary search, and somebody has already done that thing… I am an ideas person and I just get fired up with all the work we could do. It’s just a matter of time and resources because the imaging work we do is consuming.

“I always advise students to get involved in research and reach out to people early and often”

SQC: What advice would you give to young people pursuing a similar path to you?

JMA: I always advise students to get involved in research and reach out to people early and often! I think students sometimes feel that faculty members are too busy or that they don’t have time to entertain their emails, but that is not the case! We love hearing from students and seeing that passion that we had when we were young. So, get involved early and often, and talk to your mentors! If you are taking a course and you really like that professor’s research or enjoyed their lecture, ask them. Ask them about opportunities in their lab or in their field…When students have that passion, you can really see it. And when that comes along, we as faculty, are happy to help students.

SQC: That is great advice and is nice to hear faculty advocate for those students with the drive despite whatever means they must work with or things they may be struggling with. It’s great to hear that people are willing to invest in that drive and in them.

DR. ANDRONOWSKI’S RESEARCH

SQC: …Can we talk a bit more about the research? … You have had a really successful path with CIHR grant applications and other awards. Can you talk about what that grant writing process is like, what research you are doing, and any advice?

JMA: Keeping in mind that I transitioned from a US institution, even though I am Canadian, this was the first CIHR grant I applied for because the agencies there [in the US] are very different. For example, [in the US] you have the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health (NIH) which is sort of equivalent to our CIHR (Canadian Institute of Health Research), so I’ve certainly learned a lot too in the process here. The CIHR grant I received is focused on the prolonged effects of opioid use on bone remodelling. That project has two arms: the first is an ex-vivo imaging component that involves human samples from a diverse group of human samples that were organ donors from Ohio, USA.

These samples are collected from the skeleton with consent from either the donor’s themselves or their next of kin at the time of death. This sort of organ donation non-profit organization route was valuable in terms of a study sample because you have a lot of information about each donor – about 100 pages involving their health, their lifestyle, their family interviews, all this type of information. Comparatively, typically from a cadaver sample we would normally get age, sex, and cause of death… We will be using a subset of individuals from this group who were known to use opioids throughout life and assessing changes to the porosity and cellular network of bone using high resolution imaging like synchrotron radiation-based micro-Computed Tomography (SRµCT).

The human model system is ideal because it is the species, we are studying these effects, however, there are so many confounding factors and indirect effects of opioid use we can’t control because we just don’t have that information... The second arm of the study controls for indirect effects such as differences in diet, lifestyle, age, sex, and other health factors.

In terms of preparing a CIHR grant … again, I really like writing grants... I enjoy it and I never really go into it thinking it’s going to be successful or not. What I learned from that experience is …there is a big challenge with selecting appropriate committees. There are different committees that specialize in all different areas of biomedical sciences and health-related research. Finding the right match to a particular committee is the biggest challenge, I would say. My advice there would be to talk to people who have written and been successful with CIHR if they are in your area of research and pick their brain as to the committees that they applied to. You can also reach out to the program officers or program chairs of these committees for feedback on your general research idea… that aspect of fit is really critical.

SQC: That is great advice, thank you Dr. A. You do touch on the collection of donated human samples you work with. Can you tell us a little bit about that collection?

JMA: Absolutely! The collection is the Andronowski Skeletal Collection for Histological Research (ASCHR) and I began developing that in 2017 when I was in the US. It started with objectives of a particular project related to age- and sex-related changes across the lacuno-canalicular network/bone cellular network… At that point, I did a lot of reaching out, mostly to medical schools with cadaveric donation programs with the goal of acquiring a diverse sample of bone related to weight-bearing (lower limb) and bones of the thorax [non-weight bearing bones] that don’t experience the same biomechanical pressure. I developed relationships with these institutions and extended contracts for acquisition into the collection and over time, that grew to include the organ donation non-profit I mentioned in Ohio.

Since 2017, that collection has grown exponentially. It is now the biggest of its kind in the whole world, actually, which I am really proud of. And it continues to grow! Even though I am in Canada now, we have different pipelines for sample procurement now, Medical Examiner’s offices in Canada and the US as well as some of those contracts I still have in Ohio, USA. Our hope for that is to have these collaborative resources, not only for biological anthropology, but other areas of skeletal biology as well…

[Current work with the collection] aims to create slides from each of our samples in the collection and digitize them so histological images are accessible for people who cannot travel or do not have the equipment/funding to make their own slides. Access to resources can be a hurdle in anthropology given access to specialized lab equipment and funding. So, if we can make it as accessible as possible, that is the goal. Especially in [circumstances] like the pandemic when all of us were forced to stop travel, that really hindered research so if we can share resources digitally, research can continue.

SQC: That is such a wonderful accomplishment, congratulations! And thank you for talking with me today and providing so much valuable insight.

JMA: Yes, no problem, talking about these topics brings you back to why you started… Another word of advice is that even though graduate school can be hard, try not to get discouraged, use the resources that are available and talk to your professors. If students want to contact me about any of these fields, or if they have questions about my jobs or how to get involved/their foot in the door, I am always happy to talk with students.

-

Check out the Andronowski Lab Website for more info on her work.

See also Dr. Andronowski’s Faculty Page at Memorial University of Newfoundland and the Andronowski Skeletal Collection for Histological Research.

-

Dr. Andronowski’s CIHR MUN Gazette Article 2022

-

Dr. Andronowski is also on Twitter!

Email: jandronowski@mun.ca

-

This interview was conducted and transcribed by Sydney Quinn Chizmeshya, WISE GSS Director at Large (2022). This blog post was prepared by Reem Abdelrahim.

Feeling inspired? Follow us on our social media below for more!